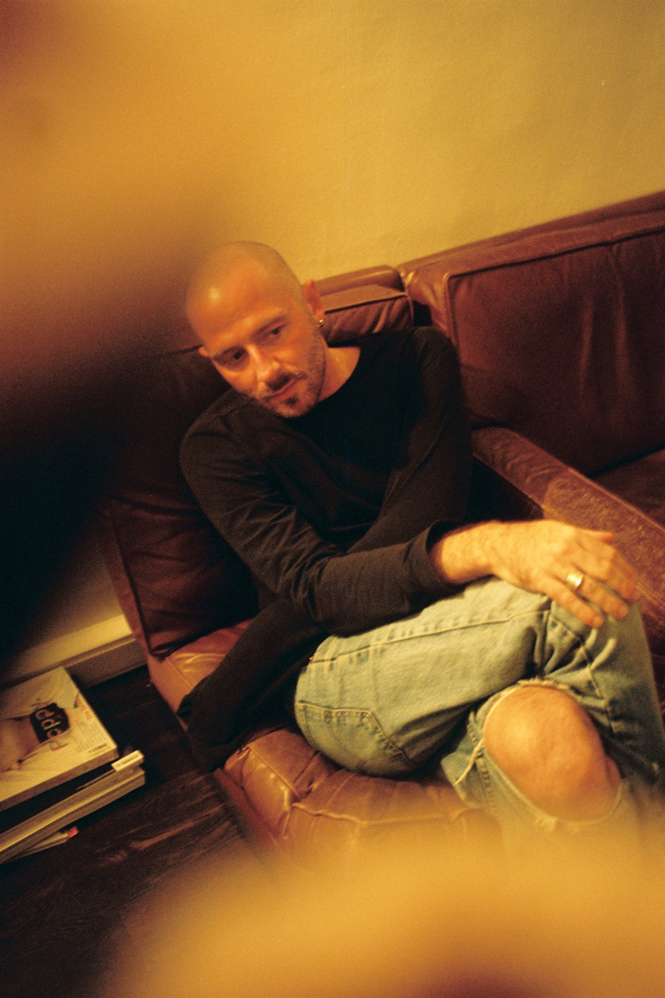

[ Interview ] Demna Gvasalia / designer

Demna Gvasalia : new king in the jungle

──Numéro Tokyo: Where were you born?

Demna Gvasalia : I was born in Ex-Soviet-Union Georgia, which is now an independent republic.

──What was it like growing up there?

Growing up under communism was a bundle of fun, as you can imagine. (Laughs.) We had absolutely nothing. Even the smallest, most worthless things were of value to us.

──How did you feel about Vladimir Putin’s 2014 annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula?

That’s a great – if somewhat unexpected – question. I can totally relate to recent events in Ukraine, because the exact same thing happened in Georgia – albeit on a smaller scale, and one that was perhaps less visible internationally. The region of Georgia where I was born was occupied by Russians back then, and it still is now. I will never be allowed to return there. Vladimir Putin took my home away from me.

──How did the political unrest manifest itself when you were growing up?

Very clearly: when I was just 12 years old, I was forced to leave the family home with just a photo album and a backpack, and escape over the mountains for two weeks.

──Wow.

I learnt certain life lessons the hard way. My family and I didn’t really care what we had or what we owned… all that mattered to us was that we were still together, and that we were still alive. Those early struggles really helped shape my worldview.

──What did your parents do for a living?

My dad ran a car wash, and my mother stayed at home to raise my brother and me. We lived in a fairly large community with an extended family of uncles, aunts and cousins, so she was kept pretty busy.

──As a child, were you more of a mummy’s boy or daddy’s boy?

It’s hard to say… I don’t think I’m a mummy’s boy or a daddy’s boy. I’m my own boy. (Laughs.) Which is the heart of the problem!

──When did you first realise you were interested in fashion?

I’ve been interested in clothes, as opposed to fashion, for as long as I can remember. As a kid, I used to love dressing up, changing clothes ten times a day and generally driving my parents crazy because they’d have to wash three different outfits every day.

──How did your own personal style evolve over the years?

When I was at school, I wore the same thing as every other kid in the Soviet Union, because there were basically three or four brands dressing the whole country. So we would customise things, to stand out from the crowd. I would chop the sleeves off my shirts, for example, or replace the white buttons with red ones… that kind of thing. I used to dress like a nerdy Soviet kid. And I had a long fringe, which didn’t help matters. I also had a fetish for white socks, which was a problem because they had to be washed all the time. When I hit my teens, the Soviet Union collapsed and it was a brave new world out there. I discovered everything at once. Raves, hip-hop, the gothic scene… In the early ’90s, in Georgia, there was an incredible mix of people trying to express their newfound independence and freedom through what they wore.

──Which set did you fit into, if any?

I’ve always had something of a multiple personality disorder, so one day I’d be dressed up as a West Coast rap star, and the next I’d be draped in full Gothic garb… I used to love the idea of using different clothes to play different characters. And I still do, to this day.

──Were you popular at school?

No, I was a bit of a black sheep… but fortunately I had a few other grey and dark grey sheep in the flock with me. So I wasn’t completely alone.

──Were you a straight-A student?

Yes, I was really good at school. I didn’t enjoy studying, but I was good at it.

──Did any traumatic experiences in the playground leave you scarred for life? You know how kids can be cruel.

Yes, I remember receiving a love letter from a guy.

──That’s hardly what I’d call traumatic.

You need to put things into context: in Georgia back then, being gay was a big drama. So I went and beat him up. It was horrible.

──Twenty years later and you’re staging fashion shows at Paris’s notorious gay sex club, Le Dépôt.

Exactly. Let’s just say that during those 20 years a lot of things changed in my outlook on life.

──When did you first realise that you preferred boys to girls, sexually?

At the age of six.

──So when you gay-bashed your school friend, you knew that you were gay yourself? Nice.

Of course I did, but I wasn’t able to accept it. Georgia is one of the most homophobic countries in the world. It was then, and it is now. I had to hide my sexuality throughout the whole of my childhood, which wasn’t easy, believe me. Oh my God. I haven’t seen a shrink about it yet, but perhaps I should! Perhaps therapy will help me to discover a new me!

──When did you decide it was time to fly the nest?

I decided to leave Georgia when I understood that I wouldn’t be able to study or work in fashion there. I’d been eager to study fashion since I was 12, and I wanted to apply for art academy, but my parents told me it was out of the question. They said that you couldn’t earn a living with fashion, and that it wasn’t a job for guys. The odds were stacked against me, so I studied economics for four years before graduating and leaving Georgia.

──Did you move directly to Belgium to pursue your studies at Antwerp’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts?

No, I spent one and a half years in Germany, where my parents lived, before moving to Belgium to follow my dreams. (Laughs.) The Antwerp Academy was one of the cheapest places to study fashion in those days, which was a huge incentive. The fashion course at the Academy only cost 500€ a year back then, I think, whereas Central Saint Martins was closer to 12,000€.

──What’s the most mortifying odd job you held as student? Did you ever scrub toilets?

I’m afraid I can’t talk about it: the job in question wasn’t so much mortifying as it was outright illegal.

──You were a drug dealer! Did you ever star in a porn movie like your fellow Antwerp Academy alumnus, the designer Bernhard Willhelm?

Ah, so you’ve heard about the porn movie! (Laughs.) I actually have a tape of it at home.

──Is it any good?

It’s quite good, but he’s not called Bernhard Willhelm in the opening credits. He used some sort of weird, German stage name for the movie. But to answer your question, no, I never starred in a porn movie. I wish!

──What did you learn at the Antwerp Academy?

The competition was really tough there: it was horrible and completely Darwinian in the sense of “Survival of the fittest”. But as they say, what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger, and ultimately the cutthroat atmosphere at the Academy helped to build me. The course itself wasn’t that great: it was very focused on creativity, but didn’t teach you anything about the business side of things – or about designing real clothes that people might actually want to wear, for that matter. If anything, the course taught you how to develop and express your own creative voice. I don’t know if that’s still the case, though. In recent years, the school seems to have lost touch and remained trapped in a sort of “Antwerp Six” time capsule, which is a pity.

──Did you actually succeed in graduating, unlike our dear friend Haider Ackermann?

I graduated with honours. Don’t ask me why, because my graduation collection was downright awful.

──What did it consist of?

It was terrible, deconstructed and weird menswear. Believe me, you wouldn’t ever want to see a man dressed like that. Nor would I, for that matter.

──Did you immediately land your first job upon graduation?

I had my first job lined up for me two months before graduating: one of my teachers, Walter [Van Beirendonck], had asked me to work with him. I spent one and a half year designing menswear with Walter, but I really wanted to branch out into womenswear so I sent a project to different houses, one of which was Maison Martin Margiela.

──What did the project consist of?

It was a whole bunch of research stuffed into a Domino’s pizza box. I wanted to do something fun, because I was so bored in Antwerp. Maison Martin Margiela called me, and ten days later I was working in Paris. I really liked the team there: we would spend all day in the studio moaning and groaning, and then we’d party all night. I spent three and a half years there, before moving to Louis Vuitton. A headhunter called me with an offer I couldn’t resist: a better position, a better salary, better working hours…And I needed a little luxury in my life at that point. I loved the idea of working for a large corporation. For the first time in my life, I wouldn’t have to take the RER train to the airport, because I’d have a driver on call.

──Who was at the creative helm of Louis Vuitton when you were working there?

I arrived during the transitional period when Marc [Jacobs] was leaving and Nicolas [Ghesquière] was arriving. So I worked with Marc for two seasons, and then with Nicolas for another two.

──If you had to choose between the two, whom would you pick?

Well, I chose: I left and started Vêtements! (Laughs.) It was interesting to see how a large company like Louis Vuitton works. When I was there, I worked on the women’s ready to wear collections, with a focus on the larger tailored pieces – the coats, jackets and outerwear. I felt that if I wanted to be fulfilled as a fashion designer, I needed to make clothes that people would actually want to own and wear. That’s where the idea of Vêtements sprung from.

──Did you launch Vêtements with the help of outside financial backing?

No, I paid for everything myself. At one point we hit the cash flow overlap that most companies are confronted with – when you’re launching production and you’re still waiting to be paid by your clients – but somehow we managed to pull through without going to the bank, getting a loan or signing up with a financial partner. The fact that we were able to overcome such hurdles was mainly thanks to our early clients who helped us out with pre-payments.

──How did you find your first clients?

My brother [Guram] takes care of the commercial side of things. Sales are his passion, and they’re what he does best. We were carried in 27 stores for the first season, which was no small feat for a start up brand.

──Working with my brother would drive me nuts.

It’s not easy. We yell at each other, and then we kiss and make up. We trust each other. Families are like that.

──I read somewhere that you’d launched Vêtements with an “international collective of seven anonymous designers”. What the hell does that mean?

It’s total bullshit. I don’t know where that piece of information came from, but it’s completely inaccurate and now it’s all over the place. For the record, we started Vêtements in my bedroom with two other designers, one of whom used to be my assistant at Vuitton. We would hang out together after work and get drunk on café terraces out of sheer professional frustration. We wanted to find a way of dressing people like us: the cool people.

──What does your bedroom look like?

It was a typical Haussmannian bedroom, but it was seriously fucked up by the time we got Vêtements off the ground. I’ve changed apartments since launching the brand: I couldn’t sleep there anymore, it was too traumatising. (Laughs.)

──To what extent are your collections inspired by what you see on the street?

I’m inspired by what I see on the street, but I’m also inspired by a variety of other things. I could be inspired by the coat that you’re wearing, for example, or by the way that you’re wearing it. There are so many things that can translate into product, for me. My aim is to dress people. I was in New York two days ago where I saw so many people wearing our stuff that I wanted to cry. I don’t want our clothes to be in Vogue; I want them to be on people’s backs.

──What do you make of the new straight-off-the-catwalk trend that’s sweeping the industry, with houses such as Burberry and Tom Ford planning to shake up the fashion calendar to make their clothes directly available to the consumer?

I was kind of annoyed because when the press started talking about rescheduling the collections, they put Tom Ford, Burberry and Vêtements in the same pot, as if three such wildly different brands had anything to do with one another in terms of strategy. Nobody really understood what came from us. What we’re going to do, basically, is switch the seasons. We will show our next ready-to-wear collection in March, but from then on we will no longer be showing during fashion week. Instead, we will adapt the schedule to our production calendar and the budgets we receive from our clients. Which means that we will have 80% of our sales budget for production, instead of 20%. Economically speaking, it makes more sense. But it also makes more sense in terms of delivery. The clothes will be in stores for five months instead of two; they will have a much longer shelf life and will therefore be more likely to sell out.

──Whose idea was it to stage Vêtements’ autumn/winter 2015-2016 show at Le Depôt?

It was my idea.

──I’ve always found it rather smelly there.

And so? It’s smelly, for sure, but at least it feels real, and it doesn’t stink of perfume.

──Who would you rather cross there in the bleak of the night: Tom Ford, Nicolas Ghesquière or Olivier Rousteing?

I’d rather not.

Vetement

vetementswebsite.com

Photo:Pierre-Ange Carlotti

Interview & Text : Philip Utz

Edit:Maki Saito